The Glass Carpets of the Silk Road

Once a master mosaicist in Soviet Kazakhstan,

Uzakbai Koshkinbaev is trying to save his murals before it’s too late.

Uzakbai Koshkinbaev is trying to save his murals before it’s too late.

In the popular imagination, mosaics are often remembered as a decorative art of the ancient world. Roman and Byzantine temples and homes often had every last surface studded with colored glass shards called tesserae, and these durable murals inspired art historians for ages. Yet few realize that mosaics were made in the 20th century with a similar plenitude, not in the Mediterranean basin but in the vast, forgotten lands behind the Iron Curtain. From the 1960s to the 1980s, Soviet artists decorated more buildings with mosaic murals than anywhere else in the world, and a man from a small village in Kazakhstan, Uzakbai Koshkinbaev, was one of the form’s most singular talents.

Koshkinbaev’s hometown of Tulkibas lies below a scenic spur of the Tien Shan mountains, a place where botanists from around the world gather every spring to hunt for exotic tulips. The tulips have been praised by poets and explorers for centuries, but Tulkibas itself is a relatively new spot on the map. Before the 1930s, Koshkinbaev’s grandparents would have lived as nomads, setting up their yurts in summer pastures called zhailau before packing up and resettling to qystau quarters for the winter. When Kazakhstan became one of the Soviet Union’s constituent republics (its second largest after Russia), this cyclical migration was brutally suspended. Stalin declared nomadism a vestage of feudalism and forced shephard families to settle permanently at their winter qystaus. Their cattle were requisitioned by the state and starved to death on mismanaged communal farms. Nearly two million died in an ensuing famine that Kazakhs call Asharshylyq.

As more Soviet citizens were settled and urbanized, the USSR embarked on a massive project of city-building. The great Kazakh Steppe, an arid flatland that stretches from Tulkibas to Siberia, had contained only a scattering of Russian-built outposts. Now the country was being planted with mining towns and industrial towns and towns for the thousands of scientists who were sent to Kazakhstan to build the Soviet space and nuclear programs. The buildings that went up were simple but efficient, assembled from standardized slabs of concrete. The spare design of Soviet modernism demanded a new approach to architectural ornamentation, and the mosaic became the socialist planners’ favorite way to dress up a facade.

Unlike their settled neighbors, the Uzbeks, whose oases were draped in turquoise tiles, the Kazakhs never had a mosaic tradition. The Russians, though, had built up a formidable expertise. Ever since Peter the Great invited the Bonafede brothers from the Vatican to open a mosaic workshop in his new capital, St. Petersburg, Russian artisans had passed down a secret recipe for a magical material called smalti. Powders and pigments went into a kiln and out came blini, “pancakes,” of opaque glass. These pancakaes of smalti, produced in a dizzying pallet, were chiseled down into tesserae, and these pressed by the millions onto the walls of Orthodox Churches. After the October Revolution, though, churches were closed and smalti making nearly disappeared. Until, that is, architects realized that these kaleidoscopic glass images were the perfect medium for the new Soviet city, a medium that felt as eternal as the utopia socialists hoped to build.

When Koshkinbaev was a teenager, he left the adobe shacks of Tulkibas for Tashkent, the region’s largest metropolis a night’s train ride away in Uzbekistan. He had impressed his teachers early on with his tulip-flooded landscape paintings, and he was chosen to study at the Benkov Art School in Uzbekistan’s capital. After graduating, the young painter stayed in Tashkent, and while furthering his studies at the Ostrovskiy Institute of Theater and Art he was introduced to one of the hottest trends in Socialist Realism - monumental’noe iskusstvo, or “Monumental Art.”

Unlike their settled neighbors, the Uzbeks, whose oases were draped in turquoise tiles, the Kazakhs never had a mosaic tradition. The Russians, though, had built up a formidable expertise. Ever since Peter the Great invited the Bonafede brothers from the Vatican to open a mosaic workshop in his new capital, St. Petersburg, Russian artisans had passed down a secret recipe for a magical material called smalti. Powders and pigments went into a kiln and out came blini, “pancakes,” of opaque glass. These pancakaes of smalti, produced in a dizzying pallet, were chiseled down into tesserae, and these pressed by the millions onto the walls of Orthodox Churches. After the October Revolution, though, churches were closed and smalti making nearly disappeared. Until, that is, architects realized that these kaleidoscopic glass images were the perfect medium for the new Soviet city, a medium that felt as eternal as the utopia socialists hoped to build.

When Koshkinbaev was a teenager, he left the adobe shacks of Tulkibas for Tashkent, the region’s largest metropolis a night’s train ride away in Uzbekistan. He had impressed his teachers early on with his tulip-flooded landscape paintings, and he was chosen to study at the Benkov Art School in Uzbekistan’s capital. After graduating, the young painter stayed in Tashkent, and while furthering his studies at the Ostrovskiy Institute of Theater and Art he was introduced to one of the hottest trends in Socialist Realism - monumental’noe iskusstvo, or “Monumental Art.”

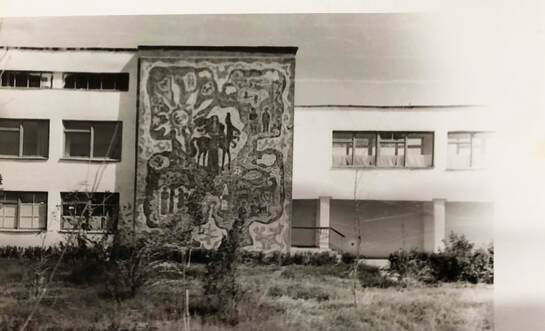

Monumental Art is what Soviet critics called a new movement at the intersection of decorative art and architecture. Monumental Artists, or “Monumentalists,” were tasked with synthesizing the built environment and the edifying image, equipped with a multi-media toolkit. At schools like Ostrovskiy, easel painters like Koshkinbaev were transformed into renaissance men, craftsmen capable of assembling everything from mosaics to relief sculptures to stained glass windows.

Yet what’s surprising about Monumental Art, at least for the outsider, is that the resulting murals weren’t simply propaganda posters in the tired idiom of Socialist Realism. The movement occupied an ambiguous position outside the world of fine art, so the restrictions that applied to the canvas no longer applied to the facade. Human figures in murals could be cartoonishly iconographic rather than realistic, because the scales and materials involved called for simplified forms. The field behind the figures was often filled with abstract, almost psychedelic, geometries that would have enraged censors of Soviet museum art. And, perhaps most striking of all, the subject matter consisted of more than farmers and factory workers (though there was plenty of that.) In Central Asian republics like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, mosaics were just as often used to glorify the region’s traditional culture. Kazakh mosaics have many more lyres and horses than Lenin heads.

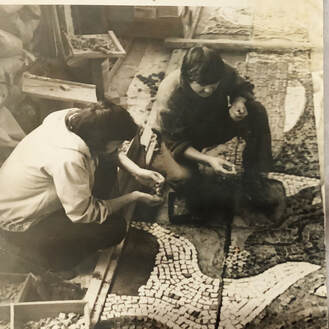

When Koshkinbaev got his first commissions in the early 1980s, there was a burgeoning interest throughout the Soviet republics in the ancient arts and crafts that had been nearly swallowed up by Stalinism, when expressions of national pride were seen as threats to the assimilationist tide of Russian-led socialism. Koshkinbaev and his peers, for example, were fascinated by nomadic carpet technologies. Just as Koshkinbaev could take smalti tiles and weave a carpet of glass, his ancestors could shear a sheep and beat the fur into fibrous mats of felt. Kazakhs used this waterproof, insulating wonder material like steppe stucco. Outside the yurt, a coat of felt shielded yurts from the fiercest blizzards, while inside the yurt, felt flowed freely from the lattice walls to the grass floor below.

The carpets and tapestries of nomads past came in many varieties, and Koshkinbaev studied them all. There was the tus kiyiz, where velvet was embroidered with silk, and the syrmaq, where snipped-up puzzle-like pieces of felt were sewn together with thick thread, forming a harmonious field of positive and negative space. But there was one style above all that Koshkinbaev would borrow again and again for his mosaics - the tekemet. To make this uniquely threadless tapestry, nomads would take a mat of felt and gingerly thumb tufts of colored sheep fur onto its surface. The haphazard tufts, traced into curling patterns, adhere to the mat through a microsopic process: when water and soap are vigorously scrubbed into the carpet, miniature burrs on the wool fibers hook like velcro and meld the piece into a cohesive whole. A tekemet seems to give off a unique vibration, because its elements don’t come together in discrete straight lines; the woolen patches bleed and blend. Viewing Koshkinbaev’s mosaics up close, inspecting the edges of their wavering forms, you find that the colored tesserae mingle just like sheep hair.

Yet what’s surprising about Monumental Art, at least for the outsider, is that the resulting murals weren’t simply propaganda posters in the tired idiom of Socialist Realism. The movement occupied an ambiguous position outside the world of fine art, so the restrictions that applied to the canvas no longer applied to the facade. Human figures in murals could be cartoonishly iconographic rather than realistic, because the scales and materials involved called for simplified forms. The field behind the figures was often filled with abstract, almost psychedelic, geometries that would have enraged censors of Soviet museum art. And, perhaps most striking of all, the subject matter consisted of more than farmers and factory workers (though there was plenty of that.) In Central Asian republics like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, mosaics were just as often used to glorify the region’s traditional culture. Kazakh mosaics have many more lyres and horses than Lenin heads.

When Koshkinbaev got his first commissions in the early 1980s, there was a burgeoning interest throughout the Soviet republics in the ancient arts and crafts that had been nearly swallowed up by Stalinism, when expressions of national pride were seen as threats to the assimilationist tide of Russian-led socialism. Koshkinbaev and his peers, for example, were fascinated by nomadic carpet technologies. Just as Koshkinbaev could take smalti tiles and weave a carpet of glass, his ancestors could shear a sheep and beat the fur into fibrous mats of felt. Kazakhs used this waterproof, insulating wonder material like steppe stucco. Outside the yurt, a coat of felt shielded yurts from the fiercest blizzards, while inside the yurt, felt flowed freely from the lattice walls to the grass floor below.

The carpets and tapestries of nomads past came in many varieties, and Koshkinbaev studied them all. There was the tus kiyiz, where velvet was embroidered with silk, and the syrmaq, where snipped-up puzzle-like pieces of felt were sewn together with thick thread, forming a harmonious field of positive and negative space. But there was one style above all that Koshkinbaev would borrow again and again for his mosaics - the tekemet. To make this uniquely threadless tapestry, nomads would take a mat of felt and gingerly thumb tufts of colored sheep fur onto its surface. The haphazard tufts, traced into curling patterns, adhere to the mat through a microsopic process: when water and soap are vigorously scrubbed into the carpet, miniature burrs on the wool fibers hook like velcro and meld the piece into a cohesive whole. A tekemet seems to give off a unique vibration, because its elements don’t come together in discrete straight lines; the woolen patches bleed and blend. Viewing Koshkinbaev’s mosaics up close, inspecting the edges of their wavering forms, you find that the colored tesserae mingle just like sheep hair.

When I first meet Uzakbai Koshkinbaev, I press his right hand between my palms, a Central Asian greeting that’s more of a clasp than a shake. He lives in the southern Kazakh city of Shymkent, in a neighborhood of single-story cottages hidden behind tall gates of sheet metal, and our taxi driver has been on the phone with Koshkinbaev’s wife, Kulsiya Turapbaeva, patiently navigating us through a maze of subtly-labeled streets to their modest family home. Koshkinbaev is 72, so we greet him as Uzakbai-Ata, or Uzakbai the Elder, though with his still-black hair kept in short, swept bangs, he looks much younger. When I press his hands, I feel how large they are, and they feel like hands meant for moulding and making things.

My partner Kuanysh and I have been on the road for nearly five weeks, crossing Kazakhstan by train and bus and Lada sedan as the late winter snowfall melts into the mud of early spring. Our goal: to document the country’s Soviet-era mosaics, or what’s left of them. We’ve already photographed a couple hundred murals, and met a dozen artists who made them. Some of them are jaded, apathetic. They treat our curiosity with suspicion. Those murals? They made them in another epoch, in a country that no longer exists, and they’ve long ago relinquished any feelings of ownership. “Oh, that mural is still standing, huh?” they say. “I forgot I even made that one,” they say. When we reach Koshkinbaev in this warm, welcoming city, that cynicism is absent. He and his wife beckon us into their home at once, as if they’ve been waiting to tell us a story.

Koshkinbaev’s face is smooth, with a seemingly healthy flush, but as we walk through the coat room and make small talk his expression remains taut and stoic,. His wife, who we call Kulsiya-apai, explains that the artist is actually in a great deal of pain. He’s had problems with his heart and with his memory, and so Kulsiya-apai, his constant caretaker, shadows him like an interpreter. Gazing around the house, my eyes widen. Just like in a yurt, there seems to be a a fear of empty space. Everywhere you look is color and pattern: felt carpets, yarn tapestries, oil paintings and clay sculptures, and every article seems to breathe and pulse, as if Keith Harring learned to weave.

In the living room, we fold our legs onto quilted futons called kope and scoot up to a low table, where Kulsiya-apai has prepared a collection of exhibits. There is a glossy brochure for Koshkinbaev’s 70th-birthday retrospective at the Shymkent Museum of Fine Arts and a teal booklet titled “Report on the Work of the Arts Fund of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, 1977-1981.” There are newspaper clippings and magazine articles pasted onto construction paper. The star attraction in this family museum is a photo album encased in military-green leather. A black-and-white photograph of a mosaic is glued to half the cover. On the other half is the artist’s name, written in the formal ordering of Soviet encyclopedias, “Koshkinbaev U.S.”: Koshkinbaev Uzakbai Seifullauly. Inside are archival photos of all of the artists’ mosaics, and I page through the book with reverence.

The day prior, we had gone to see Koshkinbaev’s masterpiece, “The Seasons,” a series of four mosaics hidden in the courtyard of a local mental hospital. When the Turkestan Province Neuropsychiatric Dispenser was built in the 1970s, psychiatry in the Soviet Union was largely a punititive tool, and thoroughly-sane political dissidents could be institutionalized indefinitely. Mental hospitals were heavily-guarded facilities, and few would have been allowed inside to admire the colorful murals decorating the grassy yard. Yet such were the absurdities of a system where zakazy, or state tenders, for monumental art were often distributed to artist collectives in exchange for kickbacks. In one cruel case, two large mosaics were installed in the capital city of Alma-Ata on a special factory. The workers must have been perplexed by the cubes of glass on the wall, as they were all blind.

The mental hospital in Shymkent had come a long way since the dark days of Soviet psychiatry, but as we wandered the halls in search of official permission to shoot the mosaics (one always needs official permission), there is still an unsettling air. Art historians with a photography project are not the hospital’s usual clientele, so we are punted up the line of command until we meet an occupied woman in a lab coat who nods at our request and sends us outside.

The mosaic is actually four mosaics, titled “Spring,” “Summer,” “Autumn” and “Winter.” At first, it’s hard to make out the subject matter. There are nearly a half million tesserae spread over the four murals, and they only attain a sense of order from a distance, like with a pointillist painting. The murals are also three stories tall, so have to step back to fit them in your field of vision. The poplar saplings we see in Koshkinbaev’s old album have grown into mature, shade-giving trees, and we squint through the trembling leaves to admire the colorful images beyond.

The mosaics, we realize, are all connected. In “Spring,” we see a golden sun arising from its slumber, and a pregnant woman standing beside a horse. In “Summer,” the sun is overhead, and the horse now carries a little boy and his grandpa. By “Autumn,” the boy is an adolescent with a steed of his own, and the sun is setting into darkness. “Winter” ends the cycle with the sun a frosty orb. The boy is now a man, setting out to hunt with an eagle on his arm.

Each season, and each mosaic, comes with a set of signs. Under the rising sun of spring we see a couple of flying cranes, whose annual migration over the Kazakh steppe heralded the new year’s thaw. Boys play outside a yurt with a newborn lamb and foal, while a young couple, intoxicated by the season of romance, stands awkwardly under a blossoming tree. By the summertime, the nursing cattle have produced a flood of dairy products, and we see a time-lapse as qymyz, or fermented mare’s milk, is whipped up in a barrel, poured into a leather bag, and ladled into bowls. In the fall, the sheep have been sheared and their wool is being rolled into felt carpets; in the only sign of Soviet modernity, a tractor sits in a field as workers pick the cotton harvest. The final panel brings the winter frosts and the nomads have retreated inside. The women pass the time by embroidering a tus kiyiz, and the man hunts foxes with his dutifully-trained bird.

The gendered division of labor, the dependence on cattle herds for sustenance, the habitation in smaller family units: in the early years of the Soviet Union, these hallmarks of traditional life were targets of large-scale social disruption, as nomads were settled into towns to work with strangers at factories and farms. By the time Koshkinbaev erected these mosaics in 1981, however, nomadism and its seasonal rhythms had been lost for a generation, long enough to engender not suspicion but nostalgia. Thereafter, late-Soviet art like “The Seasons” was complicated by an unresolved paradox, as the communist state funded eligiac odes to a lifeway destroyed by communism.

Each season, and each mosaic, comes with a set of signs. Under the rising sun of spring we see a couple of flying cranes, whose annual migration over the Kazakh steppe heralded the new year’s thaw. Boys play outside a yurt with a newborn lamb and foal, while a young couple, intoxicated by the season of romance, stands awkwardly under a blossoming tree. By the summertime, the nursing cattle have produced a flood of dairy products, and we see a time-lapse as qymyz, or fermented mare’s milk, is whipped up in a barrel, poured into a leather bag, and ladled into bowls. In the fall, the sheep have been sheared and their wool is being rolled into felt carpets; in the only sign of Soviet modernity, a tractor sits in a field as workers pick the cotton harvest. The final panel brings the winter frosts and the nomads have retreated inside. The women pass the time by embroidering a tus kiyiz, and the man hunts foxes with his dutifully-trained bird.

The gendered division of labor, the dependence on cattle herds for sustenance, the habitation in smaller family units: in the early years of the Soviet Union, these hallmarks of traditional life were targets of large-scale social disruption, as nomads were settled into towns to work with strangers at factories and farms. By the time Koshkinbaev erected these mosaics in 1981, however, nomadism and its seasonal rhythms had been lost for a generation, long enough to engender not suspicion but nostalgia. Thereafter, late-Soviet art like “The Seasons” was complicated by an unresolved paradox, as the communist state funded eligiac odes to a lifeway destroyed by communism.